Hi, readers. I have settled in a bit here in Corofin, and while life is never boring it has taken on a tinge of predictability. So I have decided to turn my attention in upcoming blogs less to memoir and more to some of the fascinating tidbits I’ve learned from my, admittedly, limited travel in Ireland. The journalist and student in me never tires of undertaking research, digging deeper, to gain a richer understanding of the places where I’ve visited. And I’d like to share some of these thoughts with you, in hopes that if you do come, or come back, to Ireland you may wish to visit these places yourself.

Chances are quite good that you know the names of literary luminaries George Bernard Show and William Butler Yeats, perhaps are familiar with some of their writings. If, like me, you by chance took a course in Irish playwrights in college, John Millington Synge and Sean O’Casey may also be familiar names. Irishmen all, they rose to prominence in the late 19th and early 20th century at a time known as the Irish Literary Revival, or Irish Renaissance. As I understand it, the literary revival was precipitated on the notion that it was time to reclaim Ireland’s rich language, culture and heritage, to elevate the lives of rank and file Irish people and revisit the lore and tales of the ancients. Many such tales came out of the oral tradition but some had been put to paper by early Christian (300-600 CE) monks who wrote not only treatises from their own religious tradition but also about those practices and stories of pre-Christian, pagan Ireland which then abounded. The Revival occurred at a time of great literary flowering and at a time when the drumbeat for Irish independence was growing to a mighty din.

Chances may not be as good, however, that you know the name of someone who was very much a central player in this revival — a pioneering folklorist who undertook to translate some of the oldest extant written stories and scoured the countryside to gather oral tales, a playwright, a novelist and short story writer, an essayist, the founder and business manager of a successful Dublin theater and a homeowner who provided literary refuge to all the men named above and more. Let me introduce you, albeit imperfectly, to Lady Augusta Gregory. For much of her life she resided at Coole Park, an estate in Gort, County Galway, no more than 25 minutes from Corofin; and although I had heard of her, I had no idea the depth and breadth of her legacy until after I’d visited there.

Gregory was born Isabella Augusta Persse in 1852, one of 13 children of a wealthy landholder who owned a 6,000-acre estate in County Galway. At the age of 28, surely an “old maid” by the standards of the time, she married a wealthy landholder who lived close by. Widower William Gregory was 35 years her senior, and it is his family who owned Coole Park. Let me digress here for a moment for those perhaps unfamiliar with the Anglo-Irish gentry of Ireland. There have been books, reams of material, written about this, and I am really a newcomer so apologies in advance for my imperfect distillation. It appears that as a result of the policies that began around the time of Henry VIII, when he divested all the monasteries of holdings, took hold under Oliver Cromwell, and was further honed following the Great Hunger (An Gorta Mor) when so many died or left Ireland, large swaths of Irish land fell into the ownership of a landed gentry class, nearly all of English descent. Some were absentee landlords while many like the Persses and the Gregorys, lived on their land. The locals worked for the gentry, and I think it fair to say that the twain rarely met. It was this world in which Gregory grew up and married.

It was not until after her husband died in 1892, when she was 40, that Gregory came into her own. She began writing – a memoir, essays, short stories, poems, most under a pseudonym or anonymously (!). Both she and WB Yeats write about the time that they met in 1897, and it is certainly true that she came out of her anonymous past to be a full-fledged published writer under her own name as a result of their lifelong friendship. Coole Park soon became what George Bernard Shaw called the “workshop of Ireland” because she invited the budding talents of the day to stay of a summer. It sounds as if it became kind of literary refuge where the luminaries (mostly men) not only wrote in peace but would then come together in the evening to discuss their work and the topics of the day. She and Yeats would go on to found the Abbey Theater in Dublin, where the plays of Shaw, Synge, O’Casey and others were performed, taking on the role of business manager, fundraiser and talent scout. She ended up writing more than 19 plays herself, many produced at the Abbey.

All of this is amazing enough, and all I rather knew in a “Jeopardy” question kind of way, but I was most taken with the part of her life I had not known – her legacy as a pioneering folklorist. It seems that Gregory not only overcame the anonymity of her gender to become a known force in the Irish Renaissance, but just as importantly she overcame the strictures of her class as she sought to give dignity and credence to native Irish men and women and their ancestral past. She writes:

“I was becoming conscious of a world close to me that I had been ignorant of. It was not now in the corners of newspapers I looked for poetic emotion, nor even to the singers in the streets. It was among farmers and potato diggers and old men in workhouses and beggars at my own door that I found what was beyond these and yet farther beyond that drawingroom poet of my childhood in the expression of love, and grief, and the pain of parting, that are the disclosure of the individual soul.”

She had known the local people all her life, but now purposefully sought to visit them in their homes, listen to their stories and write them down in her many “copy books.” The result is “Visions and Beliefs in the West of Ireland,” a collection of tales taken verbatim from her neighbors and transcribed. She divided these into categories – sea stories, seers and healers, the evil eye, witches and wizards – and presented them to an Irish world that, thanks in no small part to the Irish Renaissance, was hungry for the lore.

An example is Biddy Early, “the magic lady of Clare,” who lived in these parts in the early years of the 19th century. As Gregory began collecting the stories, she heard many about Biddy, an herbalist and healer with more than a hint of the otherworldly. Said one person: “There used surely to be enchanters in the old time, magicians and freemasons. Old Biddy Early’s power came from the same thing.” Here’s a short excerpt from the book, by one Daniel Curtin:

“Did I ever hear of Biddy Early? There’s not a man in this countryside over forty year old that hasn’t been with her some time or other. There’s a man living in that house over there was sick one time, and he went to her, and she cured him, but says she, ‘You’ll have to lose something and don’t fret after it.’ So he had a gray mare and she was going to foal, and one morning when he went out he saw the foal was born, and was lying dead by the side of the wall. So he remembered what she said to him and he didn’t fret.”

These stories came from a people marginalized for generations, whose beliefs in the old ways were as strong then as they were in ancient times. In fact, I met a woman in her 50s no more than two weeks ago who spent her childhood in the countryside around Tipperary. She told me that none of the farmers when she was growing up would dare to disturb ringforts on their lands – believed to be home to the Sidhe, the fairies. She remembers when one farmer destroyed a fort to make way for more grazing land, and his cattle became sick in droves. “It’s best to leave the fairies alone,” she said.

Even more remarkable, to my mind, Gregory agreed to take on a project translating some of the writings in Old Irish by the monks at the dawn of the Common Era. These are the earliest written records of the great sagas as well as the early oral histories of the Irish otherworld. The result of her effort includes her works “Cuchulain of Muirthenme,” about the deeds of the great Irish warrior Cuchulain (pronounced Cu Cullen); and “Gods and Fighting Men,” which chronicles the coming of the Tuatha De Danaan (pronounced TU-ah de dahn-an), the people of the goddess Danu, a magical race with supernatural powers (think Biddy Early). Earlier English translations from the Old Irish were reportedly stilted – particularly to the rank and file Irish person whose history they chronicled. Undaunted, she used a type of English she called “Kiltartanese,” a vernacular version of the language that would make her translation accessible to the average person. They were wildly successful, these books, as you can imagine. A friend of hers at the time said, ‘She did for the old Irish sagas what Mallory did for the Knights of the Round table.”

How is that for a legacy?

Gregory lived to the ripe old age of 80, dying in 1932 at Coole Park. You may recall that in my second blog I introduced you to Tom Neilan, the wonderful musician who lives near the cottage where I was quarantining just outside of Gort. It turns out his father, like his grandfather and great-grandfather before him, was a tenant at Coole Park, and he grew up playing in the woods and fields there. The house and grounds were sold to the Irish Land Commission, which demolished the house in 1941 – an act Neilan told an interviewer was “a national disgrace.” Today, there is only the barest portion of outside wall to mark where all those amazing talents once stayed and wrote. However, a magnificent copper beach tree still stands, called the “autograph tree” because Coole Park guests etched their names on the trunk. It is in her “walled garden,” a 4.5-acre tract where she grew many unusual plants and flowers and which was a solace to her. On the day I visited, families were taking advantage of a sunny day to picnic on the grounds there. It was a comforting sight.

She wrote in her journal not long before her death, “I know I have left a sheaf that contains its quota of golden grain; I have been but the reaper, the ripened ears came from the poor, the people; the sun that ripened the harvest comes from beyond the world. I can claim diligence, and love – for the work – for the people – for the Abbey – for Ireland – that ‘constraineth me’ to do such service as I may.”

I am indebted to the website Fembio, the Irish Times, coolepark.ie, oral historian Turtle Bunbury at turtlehistory.com. and Gregory herself, among others, for providing my insights into her life and times.

The grounds of the walled garden, Coole Park

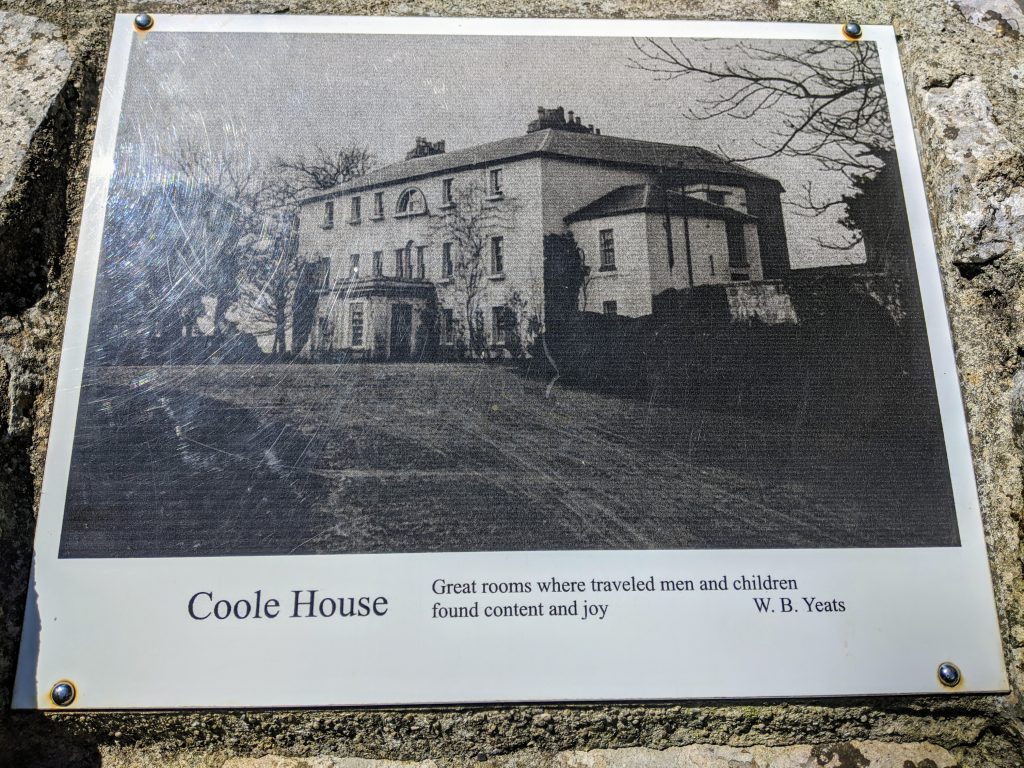

A picture depicting Coole House during Gregory’s tenure at Coole Park.

A view from the inside looking outside the wall of the grounds where Coole House once stood.

The copper beach, the “autograph tree.” On its trunk, the literary luminaries of the day carved their names.

This is taken from the outside looking in to what remains of Coole House.

Reader Comments

Thanks, Deborah!! I already e-mailed you back. Fascinating stuff 🙂

Deborah–I’m so glad you never tire of research and digging deeper! Keep it up! And somehow, Augusta Gregory reminds me of Celia Thaxter.